For some time now, Lukáš and I have been talking about security, internet advertising, user behavior analysis, etc. And we thought it would be worth putting some "hard evidence" on the table about the fact that people really have no idea what their still connected "instrument" does. So I tried it and here is the result.

Disclaimer 1: followed by a non-detailed, an amateur analysis of what our mobiles and other devices do on the Internet when we're not looking. It is meant to illustrate what roughly happens. I reserve the right to inaccurate conclusions and biased opinions (mrk).

Disclaimer 2: I'm probably slipping a little into geeky terminology and maybe I expect some knowledge from the reader that I can't explain here in a few lines. So, if you're interested in the topic, get in touch, we'll have a beer and discuss it in a little more detail (wink, wink).

As I measured

I bet you leave your cell phone on all the time. Day, night - non-stop. Have you ever wondered what the little thing is actually doing all the time? It's naive to think that nothing happens when you don't have it in your hand. I will try to illustrate it in the next few lines.

And now, how to find out, how to find out what a mobile phone is doing on the Internet "without the knowledge" of its owner? One method is to examine address translation. Computers and servers on the network do not understand addresses such as lukasbarda.cz. This is for humans. Machines need to know the so-called IP address, such as 89.221.213.142. And for presenting addresses between lukasbarda.cz and 89.221.213.142, so-called DNS or Domain Name Servers are used, which know the mapping between human www addresses and technical IP addresses. Every time you type an address into your browser, a DNS query is made and returns an IP address.

And that can be observed.

Equipment & equipment

It's been a few months (maybe even a year) since I broke out the Pi-hole on one of my Raspberry Pi's (specifically a 1 B+) at home. Ah, you don't know what I'm talking about. Digression and short explanation with links to study material:

- Raspberry Pi (https://www.raspberrypi.org) are tiny ARM computers, about the size of a credit card (or even bigger or smaller), that can run Linux and run practically anything you can think of. Many projects from home multimedia stations are built on them (https://libreelec.tv), through the automation of cultivation (fact: https://www.hackster.io/ben-eagan/raspberry-pi-automated-plant-watering-with-website-8af2dc) and retro game consoles (https://retropie.org.uk), up to various network appliances. Such as Pi-hole.

- Pi-stick (https://pi-hole.net) Yippee project and software that serves as a DNS filter with built-in functions to block unwanted domains. You can manually disable/enable which addresses are translated and which are not. You ask yourself why? Well, maybe because it might bother you that you see some ads everywhere, or you suspect that you are constantly "observed" by our big brothers Google, Facebook and others. I've written about this before.

What I measured

What I observed and observed.

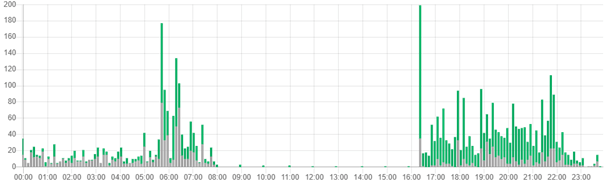

- The following figure illustrates one day of operation on my internal home network.

- We go to bed around midnight, one cell phone is on overnight, we get up around 6 a.m. and a second cell phone and laptop are added.

- After 8 o'clock we are already away from home at work, I return after 4 o'clock and my wife after 6 o'clock.

- The following graph shows the number of requests for DNS address translation in 10-minute intervals.

- The gray part of the column represents blocked requests (filtering unwanted content for us), the green part allowed translated requests.

- Between between midnight and 6:00 in the morning, the one switched-on mobile phone asked for the translation of an address almost 1000 times.

- I get up before 6, turn on my mobile, read the newspaper, etc. and it shows up on the graph as the first tall column.

- My significant other joins after 6 and at around 6:30 am watching Netflix or Youtube for breakfast, which shows up with more candles.

- Nothing for a long time during the day and then "normal" home traffic follows when we get home from work.

An attempt to interpret the results over a longer period

And who does the mobile phone talk to the most? For August 2021, they are on our network:

- 1st place occupied by optimizely.com – tools for personalization, A/B testing and web analytics.

- 2nd place: firebaseremoteconfig.googleapis.com – a tool for pushing application changes and updates without the user "ordering" them; that is, without his knowledge. Google itself says: "Firebase Remote Config is a cloud service that lets you change the behavior and appearance of your app without requiring users to download an app update."

- 3rd place: google-analytics.com – classic google analytics of user behavior everywhere.

- 4th – xth place:

- graph.facebook.com – practically any communication with Facebook is hidden behind this,

- app-measurement.com – it looks like the firebase analytics service run by Google (see 2nd place),

- edge-mqtt.facebook.com – this looks like a necessity for Facebook Messenger, I don't know what exactly it does. But when it gets blocked, Messenger stops receiving messages.

- googleadservices.com – that would advertising?

- analytics.ff.avast.com – well, yes, I have an antivirus from a well-known Czech company on my work laptop, and they also need analytical data...

- and more and more nutrients…

Well, aren't the boxes really magical? They broadcast and communicate with the environment basically all the time. And that's even if we don't look at and use them.